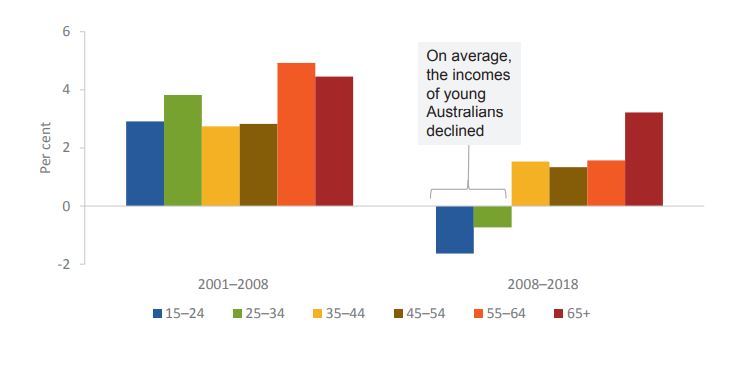

Research from the Productivity Commission (PC) found the income of Australians currently aged between 15 and 24 have similar disposable incomes to people the same age in 2001.

Between 2008 and 2015, incomes for this group fell by an average annual rate of 1.6%, while for those between 25 and 34, incomes fell by an average of 0.6% per year.

In contrast, people aged between 35 and 64 saw their incomes increase by an average of 1.4% per year, while the average annual rate of increase for retirees and people older than 65 was 3.2%.

PC Commissioner Catherine de Fontenay said the COVID-19 pandemic threatened to further increase this generational wage growth gap.

"Young people have experienced a ‘lost decade’ of income growth. This means they entered the COVID-19 crisis already on lower wages and usually with limited savings,” Ms de Fontenay said.

“Young people face discouraging prospects in a tough job market; and there is a danger they will simply give up on their aspirations as they take positions further down the jobs ladder."

Statistics suggest young people have been worst affected by job losses since the start of the crisis.

There were over 300,000 job losses among under 35 year olds since the start of the year, with an unemployment rate of 13.9% in June for 20-24 year olds.

In comparison, the unemployment rate for 35-44 year olds lifted by 1.4% in June to 5.4%.

Ms de Fontenay said there was a stark contrast between the two age groups.

“It turns out that the ‘low wage growth’ story is essentially a story about people under 35. If we look at average wage growth for those over 35, it hasn’t slowed.”

Average annual growth in real disposable incomes by age

Source: Productivity Commission

The report found the more competitive labour market post-Global Financial Crisis (GFC) affected young people the most, with companies offering lower starting wages and younger workers turning to jobs which didn't utilise their qualifications, as well as part-time work.

Ms de Fontenay said this led to long term unemployment and underemployment.

“The rise of part-time work meant that we did not see a large increase in unemployment, but many young people wanted to work more hours,” she said.

At the same time eligibility for government support schemes like Youth Allowance and Family Tax Benefits was tightened.

Futhermore, these payments aren't indexed to inflation like the Age Pension and as a result, have not grown in line with prices.

The effect of all of the above has meant young people have turned to the Bank of Mum and Dad, and stayed at home for longer.

However, Ms de Fontenay said this has only been a viable solution for middle and high income families.

“While these intra family transfers have helped cushion the fall in young people’s income, they have not been possible for all families, especially low income families,” she said.

Long term scarring in labour market

In a separate report released on Monday, the PC found the pandemic would scar employment prospects of young people for decades, and they would have to take on lower-paid and lower-quality jobs as a result.

Looking at the decade following the GFC, young people had far worse job outcomes than their older counterparts.

The report found COVID-19 would prove even worse than this period.

"Many young workers could face long-term consequences in the form of occupations lower on the jobs ladder and lower salaries than they might have expected in the early part of the century," it said.

"While young people's career prospects might have recovered once the labour market improved, such improvement is now unlikely for some time given the COVID-19 crisis.

"The fact that the weak labour market lasted for a decade means that many young workers will face long-term scarring."

Rachel Horan

Rachel Horan

William Jolly

William Jolly

Emma Duffy

Emma Duffy